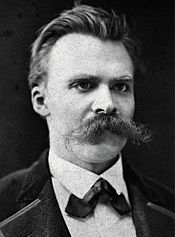

There are many kinds of courage but I want to focus in on two of them with the help of Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche is commonly known in Christian circles as the philosopher with the big mustache who declared, “god is dead.” Though that quote of his is often taken out of context that is not why I am bringing him up. In one of his essays, The Pale Criminal, he talks about two kinds of courage; the courage of the knife and courage of the blood. His ideas on courage here are important for us to have in mind as we reflect on leadership and decision making.

Nietzsche’s illustration is that of a criminal that is able to stab a person but becomes pale at the sight of the blood and the trial that follows. He has no problem stabbing a person but cannot face the natural consequence of said stabbing. Essentially he lives in denial of his desire to kill or that the action has a moral consequence. Nietzsche’s separation of courage into two kinds creates an interesting space for us to look at our own actions, consequences and motivations. For our purposes, the courage of the knife is the courage to act, to do and to accomplish. The courage of the blood is the courage to face the motivations behind the actions and the consequences to those around you. Both are vital.

Hopefully most of us are not contemplating murder but I think Nietzsche brings some interesting ideas to the fore. The idea that a person can act but not realize where that action is coming from or how that action effects others is one that I think needs more discussion in Christian circles. Overall, I don’t think that we have a problem having the courage to act. Many Christians are daring in their desire to do great things for God. We volunteer, lead, protest, witness, buy, sell, boycott, sing and work with eagerness and abandon. Generally speaking we don’t have a problem acting.

However, simply having the “courage of the knife” is not enough. Acting without reflection can manifest into all kinds of derangements or ruthlessness. A person with this kind of courage alone has no problem trampling over others in order to accomplish a task. They have no problem taking a stand for God but also pay little attention to who they might be standing on. If left unchecked they will make all manner of emotional messes but will be unwilling or unable to stick around for the cleanup. Nathan Price from “The Poisonwood Bible” would be an extreme version of this. So obsessed with “winning Africa for Jesus” he misses the point entirely.

This kind of thing can happen to anyone when they feel threatened or they get in over their heads. In order to protect ourselves from doubt we slowly shut down the “courage of the blood.” If this goes on for a long enough time we begin thinking that there is no way that we can be wrong. Rather than face ourselves we would rather project our failures onto others. I know there are seasons of life where I have done this.

This kind of thing can happen to anyone when they feel threatened or they get in over their heads. In order to protect ourselves from doubt we slowly shut down the “courage of the blood.” If this goes on for a long enough time we begin thinking that there is no way that we can be wrong. Rather than face ourselves we would rather project our failures onto others. I know there are seasons of life where I have done this. While most of us may not be completely oblivious to how our actions effect others I contend that we are probably not as aware as we think we are. In many ways we, for good or ill, allow ourselves to become blind to our own motivations. We don’t want to reflect because, lets face it, it can be painful. We may find out that we were wrong. We may find out that we used God or “the cause” to justify a poor decision. It is easier to just keep going. It takes great courage to say, “I have done wrong.” Even more to say “I wanted to do wrong.”

Outward deeds that have their root in our negligence to reflect are actually acts of cowardice. Courageous acts do not pass the buck onto God, others or “the cause” when people get hurt. Courage accepts responsibility and asks forgiveness. It faces guilt and darkness and despair. It does not coat actions with the thin veneer of self righteousness. It acts but it also takes into account where that action is coming from and where it is going. We do not need more people of action, we need more people of courage.

So how can we practically be people who are courageous? How can we be both outwardly active and inwardly aware? Here are some things that have been helpful for me:

- Carve out significant space for reflection. This is not a time to pump yourself up or internally convince yourself that you are ok. This is a time to ask the tough questions. Why did I do that? Did their criticism have a kernel of truth in it? Why is admitting guilt and asking forgiveness so difficult in this situation? Set a time limit so you don’t cut it too short or go too long. Shoot for at least 15 minutes.

- Have a circle of mentors and friends that will tell you the truth. Having people to run things by is good but you need something more than that. Mentors cannot be platforms for echoing your own ideas back at yourself. Surrounding yourself with too many “yes men” or with those who do not observe your life directly will be of little help. Find people that are willing to lovingly “hurt” you in the short term to make you better in the long run.

- Think before you act. I know this sounds simple but how often do we really do it? Assess why you want to do something and how it will effect others. What is the real reason behind your actions? You may be surprised and shocked at how effective a little mindfulness can be.

A note to any Nietzsche fans: I understand that I am taking some liberties with his ideas in order to discuss my larger point. I am borrowing heavily from Carl Jung’s assessment of The Pale Criminal. If you have further insights here please feel free to voice them.

If this article was helpful or challenging in some way feel free to share!

No comments:

Post a Comment